HfG

Alle Inhalte mit Metadaten des Vokabulars "HfG". Sie sehen nur Inhalte, für die Sie berechtigt sind.

2652 Inhalte

- Seite 1 von 221

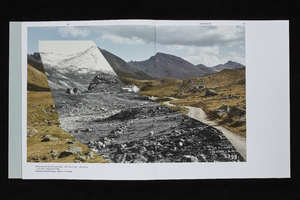

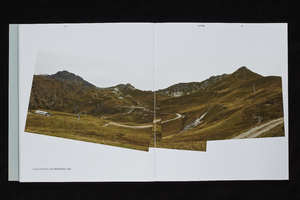

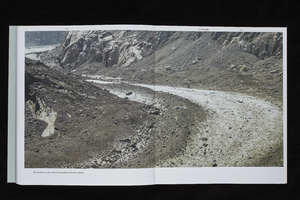

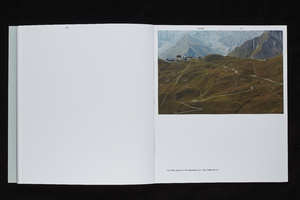

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Untertitel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Untertitel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Untertitel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Untertitel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Untertitel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Untertitel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Titel (en)

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Autor/in

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Titel

- IN BEARBEITUNG – Alpine Landschaften

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Elias Siebert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Importiert am

- 04.07.2018

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1