"Ikonographie"

| Begriff | Ikonographie |

| Metakey | Schlagworte (madek_core:keywords) |

| Typ | Keyword |

| Vokabular | Madek Core |

4 Inhalte

- Seite 1 von 1

Doppelte Ikonodulie Abstract

- Titel

- Doppelte Ikonodulie Abstract

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit dem scheinbaren Widerspruch zwischen musealer und religiöser Bildbetrachtung und der Frage, welche Kriterien diesen zu Grunde liegen. Ausgangspunkt für diese Fragestellung stellt eine Debatte dar, die in Russland geführt wird. Dort wurden sämtliche Kirchen nach der Oktoberrevolution 1917 enteignet. Der Besitz ging an den Staat über, was zur Folge hatte, dass viele der ursprünglich sakralen Objekte und Bauten zerstört, umgenutzt oder an Museen übergeben wurden. Nach dem Ende des Kommunismus in Russland wurde die Frage nach der Rückgabe dieser Besitztümer häufig gestellt. Aber erst 2007 kam es zu konkreten Planungen zu einem Gesetz zur „Übergabe des in staatlichem oder städtischem Besitz befindlichen Eigentums religiöser Zweckbestimmung an die religiösen Organisationen“ von Seiten des Staates. Dieses Gesetz sollte den Kirchen des Landes eine rechtliche Grundlage für Restitutionsforderungen bieten. Zeitgleich fühlen sich russische Museen durch das Gesetz in ihrem Bestand und in ihrer Existenz bedroht.”

„Die Frage, wem man in einer solchen Auseinandersetzung Recht geben sollte, ist durchaus schwierig: den Museen, die Kulturgüter (wie Ikonen) schützen, oder den Kirchen, für die Bilder Instrumentarien darstellen, die eine aktive Rolle im kirchlichen Ritus spielen und auch genau für diesen Zweck hergestellt wurden? Es geht also um die Frage, ob man sakrale Objekte, Kultwerke also, als Kunstwerke behandeln darf beziehungsweise wie dies zu rechtfertigen ist. Um diese Frage zu klären, ist es nötig den grundsätzlichen Umgang mit Bildern beider Institutionen zu klären. Hieraus ergeben sich auch Fragestellungen für die westlichen Museen und ihren bisherigen Gültigkeitsanspruch.”

- „Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit dem scheinbaren Widerspruch zwischen musealer und religiöser Bildbetrachtung und der Frage, welche Kriterien diesen zu Grunde liegen. Ausgangspunkt für diese Fragestellung stellt eine Debatte dar, die in Russland geführt wird. Dort wurden sämtliche Kirchen nach der Oktoberrevolution 1917 enteignet. Der Besitz ging an den Staat über, was zur Folge hatte, dass viele der ursprünglich sakralen Objekte und Bauten zerstört, umgenutzt oder an Museen übergeben wurden. Nach dem Ende des Kommunismus in Russland wurde die Frage nach der Rückgabe dieser Besitztümer häufig gestellt. Aber erst 2007 kam es zu konkreten Planungen zu einem Gesetz zur „Übergabe des in staatlichem oder städtischem Besitz befindlichen Eigentums religiöser Zweckbestimmung an die religiösen Organisationen“ von Seiten des Staates. Dieses Gesetz sollte den Kirchen des Landes eine rechtliche Grundlage für Restitutionsforderungen bieten. Zeitgleich fühlen sich russische Museen durch das Gesetz in ihrem Bestand und in ihrer Existenz bedroht.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- ‘This work deals with the apparent contradiction between museum and religious image viewing and the question of which criteria underlie these. The starting point for this question is a debate that is taking place in Russia. There, all churches were expropriated after the October Revolution in 1917. The property was transferred to the state, which meant that many of the originally sacred objects and buildings were destroyed, repurposed or handed over to museums. After the end of communism in Russia, the question of returning these possessions was frequently raised. However, it was not until 2007 that concrete plans were made by the state for a law on the ‘transfer of state-owned or municipally-owned religious property to religious organisations’. This law was intended to provide the country's churches with a legal basis for restitution claims. At the same time, Russian museums feel that their existence is threatened by the law.’

‘The question of who should be given the right in such a dispute is a difficult one: the museums, which protect cultural assets (such as icons), or the churches, for which images are instruments that play an active role in the church rite and were produced precisely for this purpose? The question is therefore whether sacred objects, i.e. works of worship, may be treated as works of art and how this can be justified. In order to clarify this question, it is necessary to clarify the fundamental handling of images in both institutions. This also raises questions for Western museums and their current claim to validity.’

- ‘This work deals with the apparent contradiction between museum and religious image viewing and the question of which criteria underlie these. The starting point for this question is a debate that is taking place in Russia. There, all churches were expropriated after the October Revolution in 1917. The property was transferred to the state, which meant that many of the originally sacred objects and buildings were destroyed, repurposed or handed over to museums. After the end of communism in Russia, the question of returning these possessions was frequently raised. However, it was not until 2007 that concrete plans were made by the state for a law on the ‘transfer of state-owned or municipally-owned religious property to religious organisations’. This law was intended to provide the country's churches with a legal basis for restitution claims. At the same time, Russian museums feel that their existence is threatened by the law.’

- Kategorie

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 17.08.2011

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Doppelte Ikonodulie Abstract

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Marco Hompes

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2011 03

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 12.01.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

everyone (dt.: alle)

- Titel

- everyone (dt.: alle)

- Schlagworte

- Titel

- everyone (dt.: alle)

- Titel (en)

- everyone

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Hanna Franke

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

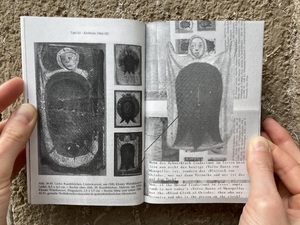

- Doppelseite des Readers zu „I used to think that I was made of Stone“.

(„everyone“, 9,5 x 15,2 cm, 36 Seiten)

- Doppelseite des Readers zu „I used to think that I was made of Stone“.

- Medien-Beschreibung (en)

- Double-page spread of the accompanying reader for “I used to think that I was made of Stone”.

(“everyone”, 9,5 x 15,2 cm, 36 pages)

- Double-page spread of the accompanying reader for “I used to think that I was made of Stone”.

- Alternativ-Text (de)

- Zwei Hände halten ein Heft vor eine Wand. Es zeigt mehrere Abbildungen in schwarz-weiß. Variationen einer Figur mit einem großen hellen Gewand, auf dem ein Gesicht abgebildet ist. Auf der rechten Seite steht unter dem vergößerten Bild der Text: "Wenn das Schweißtuch (sudarium) im leeren Grab Jesu nun nicht das heutige 'Volto Santo von Manopello' ist, sondern das 'Bluttuch von Oviedo', wer war dann Veronika und wer ist das auf dem Tuch?" auf Englisch und Deutsch.

- Alternativ-Text (en)

- Two hands holding a booklet in front of a wall. It shows several illustrations in black and white. Variations of a figure with a large light-colored robe on which a face is depicted. On the right-hand side under the enlarged image stands the text: “Now, If the Shroud (sudarium) in Jesus‘ empty tomb is not today's ’Volto Santo of Manopello‘, but the ’Blood Cloth of Oviedo', then who was Veronica and who is the person on the cloth?” in German and English.

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 15.11.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

about veronica (dt.: über veronika)

- Titel

- about veronica (dt.: über veronika)

- Schlagworte

- Titel

- about veronica (dt.: über veronika)

- Titel (en)

- about veronica

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Hanna Franke

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Alternativ-Text (de)

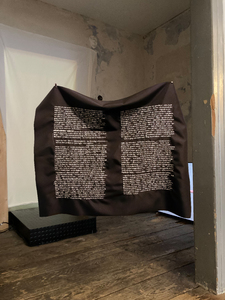

- Freigestelltes Objekt: Ein schwarzer Stoff, der Falten wirft. Auf den Stoff ist in zwei Blöcken Text mit hellem Garn gestickt. Im Hintergrund ist ein Raum mit einem Vorhang und einer schwarzen Stufe zu sehen.

- Alternativ-Text (en)

- Isolated object: A black fabric with folds. Text is embroidered on the fabric in two blocks with light-colored thread. A room with a curtain and a black step can be seen in the background.

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 02.11.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

I used to think (dt.: Ich habe immer gedacht)

- Titel

- I used to think (dt.: Ich habe immer gedacht)

- Schlagworte

- Titel

- I used to think (dt.: Ich habe immer gedacht)

- Titel (en)

- I used to think

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Hanna Franke

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Alternativ-Text (de)

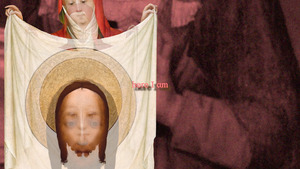

- Zu sehen ist ein Ausschnitt eines mittelalterlichen Gemäldes der heiligen Veronika. Die weiblich gelesene Person hält ein weißes Tuch vor sich, darauf ist ein Gesicht zu sehen. Es ist überblendet mit dem selben Ausschnitt. Auf diesem ist jedoch ein anderes Gesicht auf dem Tuch abgebildet. Mittig im Bild steht auf Englisch der Text „hier bin ich“.

- Alternativ-Text (en)

- A section of a medieval painting of St. Veronica can be seen. The female figure is holding a white cloth in front of her with a face on it. It is superimposed on the same detail. However, a different face is depicted on the cloth. In the center of the picture is the text “here I am” in English.

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 31.10.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1