Sereina Rothenberger

| Name | Sereina Rothenberger |

28 Inhalte

- Seite 1 von 3

Future Ruins

- Titel

- Future Ruins

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Titel

- Future Ruins

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jannis Zell

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 31.07.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Future Ruins

- Titel

- Future Ruins

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Titel

- Future Ruins

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jannis Zell

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 31.07.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Kenotaph für die Bienen

- Titel

- Kenotaph für die Bienen

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Titel

- Kenotaph für die Bienen

- Titel (en)

- Cenotaph to the bees

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jannis Zell

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- "Sie werden sie wahrscheinlich mehr als einmal in einer verlassenen Ecke Ihres Gartens in den Büschen herumflattern gesehen haben, ohne zu bemerken, dass Sie achtlos den ehrwürdigen Vorfahren beobachteten, dem wir wahrscheinlich die meisten unserer Blumen und Früchte verdanken (denn es wird tatsächlich geschätzt, dass mehr als hunderttausend Pflanzensorten verschwinden würden, wenn die Bienen sie nicht besuchen würden), und möglicherweise sogar unsere Zivilisation, denn in diesen Geheimnissen sind alle Dinge miteinander verflochten."

-Das Leben der Biene, Maurice Maeterlinck, G. Allen, London, 1901 (eigene Übersetzung)

Der Kenotaph für die Bienen ist ein Mahnmal, das an alle ausgestorbenen Bienen der Erde erinnert. Das Wachs macht es zu einem temporären Denkmal. Es ist zerbrechlich bei Berührung und Hitze.

Modell: 120 × 98 × 50 cm Styropor, Bienenwachs, Paraffin

- "Sie werden sie wahrscheinlich mehr als einmal in einer verlassenen Ecke Ihres Gartens in den Büschen herumflattern gesehen haben, ohne zu bemerken, dass Sie achtlos den ehrwürdigen Vorfahren beobachteten, dem wir wahrscheinlich die meisten unserer Blumen und Früchte verdanken (denn es wird tatsächlich geschätzt, dass mehr als hunderttausend Pflanzensorten verschwinden würden, wenn die Bienen sie nicht besuchen würden), und möglicherweise sogar unsere Zivilisation, denn in diesen Geheimnissen sind alle Dinge miteinander verflochten."

- Medien-Beschreibung (en)

- “You will probably more than once have seen her fluttering about the bushes, in a deserted corner of your garden, without realising that you were carelessly watching the venerable ancestor to whom we probably owe most of our flowers and fruits (for it is actually estimated that more than a hundred thousand varieties of plants would disappear if the bees did not visit them), and possibly even our civilization, for in these mysteries all things intertwine.”

-The Life of the Bee, Maurice Maeterlinck, G. Allen, London, 1901

The Cenotaph to the Bees is a memorial commemorating all the extinct bees of the Earth. The wax makes it a temporary monument. It is fragile to touch and heat.

Model: 120 × 98 × 50 cm Styrofoam, bees wax, paraffin

- “You will probably more than once have seen her fluttering about the bushes, in a deserted corner of your garden, without realising that you were carelessly watching the venerable ancestor to whom we probably owe most of our flowers and fruits (for it is actually estimated that more than a hundred thousand varieties of plants would disappear if the bees did not visit them), and possibly even our civilization, for in these mysteries all things intertwine.”

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 31.07.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Brunnen des wahren Glaubens

- Titel

- Brunnen des wahren Glaubens

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Titel

- Brunnen des wahren Glaubens

- Titel (en)

- Well of True Belief

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jannis Zell

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- "Obwohl wir in einer technologisch fortgeschrittenen Gesellschaft leben, ist der Aberglaube so weit verbreitet wie eh und je. Aberglaube ist das natürliche Ergebnis mehrerer gut verstandener psychologischer Prozesse, darunter unsere menschliche Sensibilität für Zufälle, eine Vorliebe für die Entwicklung von Ritualen, um die Zeit zu füllen (um die Nerven, die Ungeduld oder beides zu bekämpfen), unsere Bemühungen, mit Unsicherheiten umzugehen, das Bedürfnis nach Kontrolle und vieles mehr."

-Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition, Stuart A. Vyse. (eigene Übersetzung)

Der Brunnen des wahren Glaubens ist ein digitaler Wunschbrunnen. Er ist das erste Denkmal, das auf dem Mars errichtet wurde.

Jetzt wünschen wir uns Nebel und Tropfen und Pfützen und dass der rote Boden durchnässt wird. Nach Flaschen und Duschen und Toiletten und Fensterputzern und Coca Cola light mit Eiswürfeln; nach Schwimmen und Suppe und Pools und Brunnen und Quellen.

Modell: 60 × 126 × 83 cm Styropor, Gips, Ton, Pigmente

- "Obwohl wir in einer technologisch fortgeschrittenen Gesellschaft leben, ist der Aberglaube so weit verbreitet wie eh und je. Aberglaube ist das natürliche Ergebnis mehrerer gut verstandener psychologischer Prozesse, darunter unsere menschliche Sensibilität für Zufälle, eine Vorliebe für die Entwicklung von Ritualen, um die Zeit zu füllen (um die Nerven, die Ungeduld oder beides zu bekämpfen), unsere Bemühungen, mit Unsicherheiten umzugehen, das Bedürfnis nach Kontrolle und vieles mehr."

- Medien-Beschreibung (en)

- “Although we live in a technologically advanced society, superstition is as widespread as it has ever been. Superstitions, are the natural result of several well-understood psychological processes, including our human sensitivity to coincidence, a penchant for developing rituals to fill time (to battle nerves, impatience, or both), our efforts to cope with uncertainty, the need for control, and more.”

-Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition, Stuart A. Vyse.

The Well of True Belief is a digital wishing well. It is the first monument to have been erected on Mars. shifting boundaries between our bodies and the external world.

Now we wish for fog and drips and drops and puddles and for the red ground to get soaked. For bottles and showers and toilets and window cleaners and Coca Cola light with ice cubes; for swimming and soup and pools and fountains and wells.

Model: 60 × 126 × 83 cm Styrofoam, gypsum, clay, pigments

- “Although we live in a technologically advanced society, superstition is as widespread as it has ever been. Superstitions, are the natural result of several well-understood psychological processes, including our human sensitivity to coincidence, a penchant for developing rituals to fill time (to battle nerves, impatience, or both), our efforts to cope with uncertainty, the need for control, and more.”

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 31.07.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Future Ruins

- Titel

- Future Ruins

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Titel

- Future Ruins

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jannis Zell

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 31.07.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

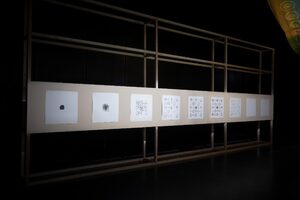

all the things you are.

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Großes Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Maxim Weirich

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 14.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

all the things you are.

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Großes Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Maxim Weirich

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 14.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

all the things you are.

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Großes Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Maxim Weirich

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 14.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

all the things you are.

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Großes Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Maxim Weirich

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 14.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

all the things you are.

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Großes Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Maxim Weirich

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 14.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

all the things you are.

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Autor/in

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Großes Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Titel

- all the things you are.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Maxim Weirich

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 14.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Seeing With Four Eyes

- Titel

- Seeing With Four Eyes

- Titel (en)

- Seeing With Four Eyes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Die Ausstellung "Seeing With Four Eyes" verfolgt die Objektbiografie der Statue Ngonnso' aus Kamerun durch verschiedene geografische, zeitliche und institutionelle Kontexte. Dieser erste Satz ist bereits fehlerhaft. Ist Statue überhaupt ein angemessener Begriff, um eine Figur zu beschreiben, die für die einen ein Lebewesen darstellt, während andere sie lediglich als Beispiel für materielle Kultur betrachten? Und ist Biografie der richtige Begriff, um das Leben eines Artefakts zu beschreiben? Ist sie an ihr materielles Wesen gebunden oder existiert sie schon lange bevor sie aus Holz geschnitzt wurde und lange nachdem sie von Termiten gefressen wurde oder in einem brennenden Museum verloren ging? In dem Bestreben, mehr über Ngonnso' zu erfahren, beschloss ich, sie bei ihrem Namen zu nennen und damit nicht vorzuschreiben, was sie ist. Ich habe versucht, die Fragmente einer Geschichte zu sammeln, die sich nicht zu einem Ganzen zusammenfügen lassen. Ich verfolgte Fäden, die bis zur Entstehungszeit zurückreichen, zu Strafexpeditionen und Kriegshandlungen des deutschen Kolonialreichs, zu Kulturfesten in Kamerun und Europa und zu einem Museum, das versucht, mit seiner Sammlung zurechtzukommen. Ich habe mit Menschen gesprochen, die sich entweder mit Ngonnso' selbst oder mit den Kampagnen, nationalen Gesetzen und der Politik beschäftigt haben, die sie beeinflusst haben und weiterhin beeinflussen. Ngonnso' befindet sich in einem Schwebezustand: Sie wird im Frühjahr 2019 von einem Museumsdepot am Rande Berlins in eine neue Museumseinrichtung im Stadtzentrum transportiert und damit erneut von einem gelagerten Objekt in ein Ausstellungsobjekt verwandelt. Zugleich ist sie Gegenstand laufender Restitutionsverhandlungen zwischen dem Oberhäuptling des Königreichs Nso', Fon Sehm Mbinglo I, dem Staat Kamerun, dem Ethnologischen Museum Berlin und dem deutschen Staat. "Seeing With Four Eyes" bietet einen Raum, um über diese Einheit in ihren vielfältigen und widersprüchlichen Dimensionen zu reflektieren.

- Beschreibung (en)

- The exhibition "Seeing With Four Eyes" follows the object biography of the statue Ngonnso’ from Cameroon through different geographical, temporal and institutional contexts. This first sentence is already flawed. Is statue even an adequate term to describe a figure that represents a living being to some people, while others merely see it as an example of material culture? And is biography the right term to describe the life of an artifact? Is it bound to its material being or does it exist well before it is carved out of wood and long after it is eaten by termites or lost in a burning museum? In the endeavour to learn more about Ngonnso’, I decided to call her by her name, thereby not predefining what she is. I tried to gather the fragments of a story that do not form a whole. I followed threads that go back to the time of creation, to punitive expeditions and acts of war carried out by the German colonial empire, cultural festivals in Cameroon and Europe, and to a museum trying to come to terms with its collection. I talked to people who have engaged either with Ngonnso’ herself or with the campaigns, national laws, and politics that have influenced and continue to influence her. Ngonnso’ is in a state of limbo: she will be transported from a museum depot in the outskirts of Berlin to a new museum institution in the city centre in the spring of 2019, once again being transformed from a stored object into an exhibition object. At the same time, she is subject of ongoing restitution negotiations between the paramount chief of the kingdom Nso’, Fon Sehm Mbinglo I, the state of Cameroon, the Ethnological Museum Berlin and the German state. "Seeing With Four Eyes" offers a space to reflect upon this entity through its multiple and contradictory dimensions.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 14.11.2018 - 16.11.2018

- Sprache

- Dauer

- 14-18 Uhr

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Lichtbrücke

- Stadt

- Land

- Titel

- Seeing With Four Eyes

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Carlo Siegfried

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 24.05.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1