"Kunstwissenschaft und Medienphilosophie"

| Begriff | Kunstwissenschaft und Medienphilosophie |

| Metakey | Fachgruppe (institution:field_of_study) |

| Typ | Keyword |

| Vokabular | HfG |

50 Inhalte

- Seite 1 von 5

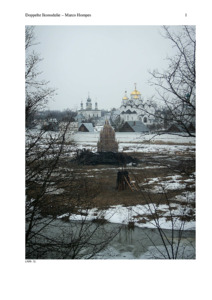

Doppelte Ikonodulie Deckblatt

- Titel

- Doppelte Ikonodulie Deckblatt

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit dem scheinbaren Widerspruch zwischen musealer und religiöser Bildbetrachtung und der Frage, welche Kriterien diesen zu Grunde liegen. Ausgangspunkt für diese Fragestellung stellt eine Debatte dar, die in Russland geführt wird. Dort wurden sämtliche Kirchen nach der Oktoberrevolution 1917 enteignet. Der Besitz ging an den Staat über, was zur Folge hatte, dass viele der ursprünglich sakralen Objekte und Bauten zerstört, umgenutzt oder an Museen übergeben wurden. Nach dem Ende des Kommunismus in Russland wurde die Frage nach der Rückgabe dieser Besitztümer häufig gestellt. Aber erst 2007 kam es zu konkreten Planungen zu einem Gesetz zur „Übergabe des in staatlichem oder städtischem Besitz befindlichen Eigentums religiöser Zweckbestimmung an die religiösen Organisationen“ von Seiten des Staates. Dieses Gesetz sollte den Kirchen des Landes eine rechtliche Grundlage für Restitutionsforderungen bieten. Zeitgleich fühlen sich russische Museen durch das Gesetz in ihrem Bestand und in ihrer Existenz bedroht.”

„Die Frage, wem man in einer solchen Auseinandersetzung Recht geben sollte, ist durchaus schwierig: den Museen, die Kulturgüter (wie Ikonen) schützen, oder den Kirchen, für die Bilder Instrumentarien darstellen, die eine aktive Rolle im kirchlichen Ritus spielen und auch genau für diesen Zweck hergestellt wurden? Es geht also um die Frage, ob man sakrale Objekte, Kultwerke also, als Kunstwerke behandeln darf beziehungsweise wie dies zu rechtfertigen ist. Um diese Frage zu klären, ist es nötig den grundsätzlichen Umgang mit Bildern beider Institutionen zu klären. Hieraus ergeben sich auch Fragestellungen für die westlichen Museen und ihren bisherigen Gültigkeitsanspruch.”

- „Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit dem scheinbaren Widerspruch zwischen musealer und religiöser Bildbetrachtung und der Frage, welche Kriterien diesen zu Grunde liegen. Ausgangspunkt für diese Fragestellung stellt eine Debatte dar, die in Russland geführt wird. Dort wurden sämtliche Kirchen nach der Oktoberrevolution 1917 enteignet. Der Besitz ging an den Staat über, was zur Folge hatte, dass viele der ursprünglich sakralen Objekte und Bauten zerstört, umgenutzt oder an Museen übergeben wurden. Nach dem Ende des Kommunismus in Russland wurde die Frage nach der Rückgabe dieser Besitztümer häufig gestellt. Aber erst 2007 kam es zu konkreten Planungen zu einem Gesetz zur „Übergabe des in staatlichem oder städtischem Besitz befindlichen Eigentums religiöser Zweckbestimmung an die religiösen Organisationen“ von Seiten des Staates. Dieses Gesetz sollte den Kirchen des Landes eine rechtliche Grundlage für Restitutionsforderungen bieten. Zeitgleich fühlen sich russische Museen durch das Gesetz in ihrem Bestand und in ihrer Existenz bedroht.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- ‘This work deals with the apparent contradiction between museum and religious image viewing and the question of which criteria underlie these. The starting point for this question is a debate that is taking place in Russia. There, all churches were expropriated after the October Revolution in 1917. The property was transferred to the state, which meant that many of the originally sacred objects and buildings were destroyed, repurposed or handed over to museums. After the end of communism in Russia, the question of returning these possessions was frequently raised. However, it was not until 2007 that concrete plans were made by the state for a law on the ‘transfer of state-owned or municipally-owned religious property to religious organisations’. This law was intended to provide the country's churches with a legal basis for restitution claims. At the same time, Russian museums feel that their existence is threatened by the law.’

‘The question of who should be given the right in such a dispute is a difficult one: the museums, which protect cultural assets (such as icons), or the churches, for which images are instruments that play an active role in the church rite and were produced precisely for this purpose? The question is therefore whether sacred objects, i.e. works of worship, may be treated as works of art and how this can be justified. In order to clarify this question, it is necessary to clarify the fundamental handling of images in both institutions. This also raises questions for Western museums and their current claim to validity.’

- ‘This work deals with the apparent contradiction between museum and religious image viewing and the question of which criteria underlie these. The starting point for this question is a debate that is taking place in Russia. There, all churches were expropriated after the October Revolution in 1917. The property was transferred to the state, which meant that many of the originally sacred objects and buildings were destroyed, repurposed or handed over to museums. After the end of communism in Russia, the question of returning these possessions was frequently raised. However, it was not until 2007 that concrete plans were made by the state for a law on the ‘transfer of state-owned or municipally-owned religious property to religious organisations’. This law was intended to provide the country's churches with a legal basis for restitution claims. At the same time, Russian museums feel that their existence is threatened by the law.’

- Kategorie

- Datierung

- 17.08.2011

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Doppelte Ikonodulie Deckblatt

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Marco Hompes

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2011 03

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 12.01.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Doppelte Ikonodulie Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Titel

- Doppelte Ikonodulie Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit dem scheinbaren Widerspruch zwischen musealer und religiöser Bildbetrachtung und der Frage, welche Kriterien diesen zu Grunde liegen. Ausgangspunkt für diese Fragestellung stellt eine Debatte dar, die in Russland geführt wird. Dort wurden sämtliche Kirchen nach der Oktoberrevolution 1917 enteignet. Der Besitz ging an den Staat über, was zur Folge hatte, dass viele der ursprünglich sakralen Objekte und Bauten zerstört, umgenutzt oder an Museen übergeben wurden. Nach dem Ende des Kommunismus in Russland wurde die Frage nach der Rückgabe dieser Besitztümer häufig gestellt. Aber erst 2007 kam es zu konkreten Planungen zu einem Gesetz zur „Übergabe des in staatlichem oder städtischem Besitz befindlichen Eigentums religiöser Zweckbestimmung an die religiösen Organisationen“ von Seiten des Staates. Dieses Gesetz sollte den Kirchen des Landes eine rechtliche Grundlage für Restitutionsforderungen bieten. Zeitgleich fühlen sich russische Museen durch das Gesetz in ihrem Bestand und in ihrer Existenz bedroht.”

„Die Frage, wem man in einer solchen Auseinandersetzung Recht geben sollte, ist durchaus schwierig: den Museen, die Kulturgüter (wie Ikonen) schützen, oder den Kirchen, für die Bilder Instrumentarien darstellen, die eine aktive Rolle im kirchlichen Ritus spielen und auch genau für diesen Zweck hergestellt wurden? Es geht also um die Frage, ob man sakrale Objekte, Kultwerke also, als Kunstwerke behandeln darf beziehungsweise wie dies zu rechtfertigen ist. Um diese Frage zu klären, ist es nötig den grundsätzlichen Umgang mit Bildern beider Institutionen zu klären. Hieraus ergeben sich auch Fragestellungen für die westlichen Museen und ihren bisherigen Gültigkeitsanspruch.”

- „Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit dem scheinbaren Widerspruch zwischen musealer und religiöser Bildbetrachtung und der Frage, welche Kriterien diesen zu Grunde liegen. Ausgangspunkt für diese Fragestellung stellt eine Debatte dar, die in Russland geführt wird. Dort wurden sämtliche Kirchen nach der Oktoberrevolution 1917 enteignet. Der Besitz ging an den Staat über, was zur Folge hatte, dass viele der ursprünglich sakralen Objekte und Bauten zerstört, umgenutzt oder an Museen übergeben wurden. Nach dem Ende des Kommunismus in Russland wurde die Frage nach der Rückgabe dieser Besitztümer häufig gestellt. Aber erst 2007 kam es zu konkreten Planungen zu einem Gesetz zur „Übergabe des in staatlichem oder städtischem Besitz befindlichen Eigentums religiöser Zweckbestimmung an die religiösen Organisationen“ von Seiten des Staates. Dieses Gesetz sollte den Kirchen des Landes eine rechtliche Grundlage für Restitutionsforderungen bieten. Zeitgleich fühlen sich russische Museen durch das Gesetz in ihrem Bestand und in ihrer Existenz bedroht.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- ‘This work deals with the apparent contradiction between museum and religious image viewing and the question of which criteria underlie these. The starting point for this question is a debate that is taking place in Russia. There, all churches were expropriated after the October Revolution in 1917. The property was transferred to the state, which meant that many of the originally sacred objects and buildings were destroyed, repurposed or handed over to museums. After the end of communism in Russia, the question of returning these possessions was frequently raised. However, it was not until 2007 that concrete plans were made by the state for a law on the ‘transfer of state-owned or municipally-owned religious property to religious organisations’. This law was intended to provide the country's churches with a legal basis for restitution claims. At the same time, Russian museums feel that their existence is threatened by the law.’

‘The question of who should be given the right in such a dispute is a difficult one: the museums, which protect cultural assets (such as icons), or the churches, for which images are instruments that play an active role in the church rite and were produced precisely for this purpose? The question is therefore whether sacred objects, i.e. works of worship, may be treated as works of art and how this can be justified. In order to clarify this question, it is necessary to clarify the fundamental handling of images in both institutions. This also raises questions for Western museums and their current claim to validity.’

- ‘This work deals with the apparent contradiction between museum and religious image viewing and the question of which criteria underlie these. The starting point for this question is a debate that is taking place in Russia. There, all churches were expropriated after the October Revolution in 1917. The property was transferred to the state, which meant that many of the originally sacred objects and buildings were destroyed, repurposed or handed over to museums. After the end of communism in Russia, the question of returning these possessions was frequently raised. However, it was not until 2007 that concrete plans were made by the state for a law on the ‘transfer of state-owned or municipally-owned religious property to religious organisations’. This law was intended to provide the country's churches with a legal basis for restitution claims. At the same time, Russian museums feel that their existence is threatened by the law.’

- Kategorie

- Datierung

- 17.08.2011

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Doppelte Ikonodulie Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Marco Hompes

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2011 03

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 12.01.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Fernand Léger und Ballet Mécanique (Deckblatt)

- Titel

- Fernand Léger und Ballet Mécanique (Deckblatt)

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- "Ballet Mecanique ist zu einer Zeit entstanden, die als Höhepunkt, und immer wieder auch als Wendepunkt in Légers Malerei verstanden wird. Der Film fügt sich nicht nur in seine künstlerische Konzeption ein, sondern hat diese auch zum Thema. Ballet Mécanique ist ein Manifest, nicht nur für seine Kunst, sondern auch für das Kino. Wie bei seinen Literatenfreunden ist Légers intensive Auseinandersetzung mit dem Kino von einer doppelten Intention geprägt, von dere Hinwendung zu dem jungen Medium als potentiellen Mittel, die eigene Kunst zu reformieren, und vom Entwurf eines neuen Konzepts von Film, der seinerseits durch die gestalterische Intervention von Dichtern und Malern zu seinen eigenen Ausdrucksmitteln findet."

- Beschreibung (en)

- "Ballet Mecanique was created at a time that is seen as a high point, and repeatedly as a turning point, in Léger's painting. The film not only fits into his artistic conception, but also has it as its theme. Ballet Mécanique is a manifesto, not only for his art, but also for the cinema. As with his literary friends, Léger's intensive engagement with the cinema is characterisedby a dual intention: a turn towards the young medium as a potential means of reforming his own art, and the creation of a new concept of film, which in turn finds its own means of expression through the creative intervention of poets and painters."

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- Juli 1997

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Fernand Léger und Ballet Mécanique (Deckblatt)

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Barbara Filser

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 1997 02

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 20.02.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Fernand Léger und Ballet Mécanique (Inhaltsverzeichnis)

- Titel

- Fernand Léger und Ballet Mécanique (Inhaltsverzeichnis)

- Untertitel

- Film als Kunst, Filmkunst, Film und Kunst

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- "Ballet Mecanique ist zu einer Zeit entstanden, die als Höhepunkt, und immer wieder auch als Wendepunkt in Légers Malerei verstanden wird. Der Film fügt sich nicht nur in seine künstlerische Konzeption ein, sondern hat diese auch zum Thema. Ballet Mécanique ist ein Manifest, nicht nur für seine Kunst, sondern auch für das Kino. Wie bei seinen Literatenfreunden ist Légers intensive Auseinandersetzung mit dem Kino von einer doppelten Intention geprägt, von dere Hinwendung zu dem jungen Medium als potentiellen Mittel, die eigene Kunst zu reformieren, und vom Entwurf eines neuen Konzepts von Film, der seinerseits durch die gestalterische Intervention von Dichtern und Malern zu seinen eigenen Ausdrucksmitteln findet."

- Beschreibung (en)

- "Ballet Mecanique was created at a time that is seen as a high point, and repeatedly as a turning point, in Léger's painting. The film not only fits into his artistic conception, but also has it as its theme. Ballet Mécanique is a manifesto, not only for his art, but also for the cinema. As with his literary friends, Léger's intensive engagement with the cinema is characterisedby a dual intention: a turn towards the young medium as a potential means of reforming his own art, and the creation of a new concept of film, which in turn finds its own means of expression through the creative intervention of poets and painters."

- Kategorie

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- Juli 1997

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Stadt

- Titel

- Fernand Léger und Ballet Mécanique (Inhaltsverzeichnis)

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Barbara Filser

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 1997 02

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 03.08.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Inhaltverzeichnis - Who cares?

- Titel

- Inhaltverzeichnis - Who cares?

- Titel (en)

- Who cares?

- Untertitel des Projekts/Werks (en)

- Digital sociality, care infrastructure and convivial technology

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Die Hackerkultur verbindet Theorie und Praxis (nach hand-on Prinzipien) und einen neuen Ansatz für Kulturmaterialien (»information wants to be free«), der nicht nur eine andere Epistemologie, sondern auch einen neuen politischen Diskurs über Digitalität, Geräte und Menschen impliziert. Das Verhältnis zwischen Technik und Politik dieser Gruppe wird im ersten Kapitel analysiert: Zuerst wird die Entstehung proprietärer Software betrachtet, dann die Unterschiede zwischen Open Source und freier Software, und wie im letzten die Privateigentum und die soziale Beziehung zwischen Programmen, Benutzern und Entwicklern radikal in Frage gestellt werden. Später wird diese Beziehung anhand von Hanna Arendts _Die conditio humana_ in Bezug auf Arbeit, Herstellen und Handlen, Notwendigkeit und Freiheit, die die Bedingungen für Politik schaffen, weiter diskutiert. Im zweiten Kapitel wird das Konzept der Konvivialität (Ivan Illich) vorgestellt und diskutiert. Diese Idee wird später in der Wartung als infrastrukturelle Vorsorge weiterentwickelt und als ein zentrales Element digitaler Technologien vorgeschlagen, das weiter diskutiert werden sollte. Diese Konstellation des Denkens und Handelns, des Spielens und Lernens, des Experimentierens und der Übernahme von Verantwortung sowie der Politik und der sozialen Beziehungen sollte in der Technologiedebatte eine wichtige Rolle spielen.

- Beschreibung (en)

- Hacker culture connects theory and praxis (following hand-on principles) and a new approach to culture materials (»information wants to be free«), that implies not only a different epistemology, but also a new political discourse on digitality, devices, and people. The relation between technic and politic of this group is analyzed in the first chapter: first focusing on the emergence of proprietary software; then considering the differences between open source and free software, the last one challenging radically the notion of private property and the social relation among programs, users, and developers. Later on, reading Hanna Arendts "The Human condition", the relation will be further discussed in terms of labor, work and action, necessity and freedom, which establish the conditions for politics. In the second chapter, the concept of conviviality (Ivan Illich) is introduced and discussed. This idea is later developed in maintenance as infrastructural care and proposed as a central element of digital technologies that should be further discussed. This constellation of thinking and acting, playing and learning, experimenting and taking responsibility, as well as politics and social relations should play a prominent role in the debate about technology.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 30.09.2023

- Sprache

- Titel

- Inhaltverzeichnis - Who cares?

- Titel (en)

- Index- Who Cares

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Víctor Fancelli Capdevila

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- Inhaltverzeichnis von Who Cares?

- Medien-Beschreibung (en)

- Index of Who cares?

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 02.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Abstract

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Abstract

- Untertitel

- antidogmatische Kunst als gesellschaftliches Potenzial

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

„Dort, wo Altes durch Neues herausgefordert wird. Dort, wo Kunst und Theater auf das alltägliche und das politische Leben treffen. Nicht umsonst forderten Künstler wiederholt die Annäherung von Kunst und Leben. Denn dort, wo beides aufeinander prallt, findet Auseinandersetzung statt. Dabei ist es nicht wichtig, was Kunst genau ist und wo sie anfängt oder aufhört. Relevant ist, dass Brüche geschaffen werden im reibungslosen Ablauf eines problematischen Systems. Es geht um eine Fraktur der Erwartung, um eine Unterbrechung des Gewohnten. Diese Strategie der Unterbrechung ist interessant für die vorliegende Arbeit.”

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

‘Where the old is challenged by the new. Where art and theatre meet everyday and political life. It is not for nothing that artists have repeatedly called for the convergence of art and life. Because where the two collide, confrontation takes place. It is not important what exactly art is and where it begins or ends. What is relevant is that breaks are created in the smooth running of a problematic system. It is about a fracture of expectation, an interruption of the familiar. This strategy of interruption is interesting for the present work.’

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 10.07.2014

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Abstract

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Seraphine Meya

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2014 01

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 30.03.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Deckblatt

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Deckblatt

- Untertitel

- antidogmatische Kunst als gesellschaftliches Potenzial

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

„Dort, wo Altes durch Neues herausgefordert wird. Dort, wo Kunst und Theater auf das alltägliche und das politische Leben treffen. Nicht umsonst forderten Künstler wiederholt die Annäherung von Kunst und Leben. Denn dort, wo beides aufeinander prallt, findet Auseinandersetzung statt. Dabei ist es nicht wichtig, was Kunst genau ist und wo sie anfängt oder aufhört. Relevant ist, dass Brüche geschaffen werden im reibungslosen Ablauf eines problematischen Systems. Es geht um eine Fraktur der Erwartung, um eine Unterbrechung des Gewohnten. Diese Strategie der Unterbrechung ist interessant für die vorliegende Arbeit.”

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

‘Where the old is challenged by the new. Where art and theatre meet everyday and political life. It is not for nothing that artists have repeatedly called for the convergence of art and life. Because where the two collide, confrontation takes place. It is not important what exactly art is and where it begins or ends. What is relevant is that breaks are created in the smooth running of a problematic system. It is about a fracture of expectation, an interruption of the familiar. This strategy of interruption is interesting for the present work.’

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 10.07.2014

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Deckblatt

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Seraphine Meya

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2014 01

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 30.03.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Konstruktive Unterbrechungen (geschw.)

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen (geschw.)

- Untertitel

- antidogmatische Kunst als gesellschaftliches Potenzial

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

„Dort, wo Altes durch Neues herausgefordert wird. Dort, wo Kunst und Theater auf das alltägliche und das politische Leben treffen. Nicht umsonst forderten Künstler wiederholt die Annäherung von Kunst und Leben. Denn dort, wo beides aufeinander prallt, findet Auseinandersetzung statt. Dabei ist es nicht wichtig, was Kunst genau ist und wo sie anfängt oder aufhört. Relevant ist, dass Brüche geschaffen werden im reibungslosen Ablauf eines problematischen Systems. Es geht um eine Fraktur der Erwartung, um eine Unterbrechung des Gewohnten. Diese Strategie der Unterbrechung ist interessant für die vorliegende Arbeit.”

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

‘Where the old is challenged by the new. Where art and theatre meet everyday and political life. It is not for nothing that artists have repeatedly called for the convergence of art and life. Because where the two collide, confrontation takes place. It is not important what exactly art is and where it begins or ends. What is relevant is that breaks are created in the smooth running of a problematic system. It is about a fracture of expectation, an interruption of the familiar. This strategy of interruption is interesting for the present work.’

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 10.07.2014

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen (geschw.)

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Seraphine Meya

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- censored version / zensierte Version

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2014 01

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 30.03.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Untertitel

- antidogmatische Kunst als gesellschaftliches Potenzial

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

„Dort, wo Altes durch Neues herausgefordert wird. Dort, wo Kunst und Theater auf das alltägliche und das politische Leben treffen. Nicht umsonst forderten Künstler wiederholt die Annäherung von Kunst und Leben. Denn dort, wo beides aufeinander prallt, findet Auseinandersetzung statt. Dabei ist es nicht wichtig, was Kunst genau ist und wo sie anfängt oder aufhört. Relevant ist, dass Brüche geschaffen werden im reibungslosen Ablauf eines problematischen Systems. Es geht um eine Fraktur der Erwartung, um eine Unterbrechung des Gewohnten. Diese Strategie der Unterbrechung ist interessant für die vorliegende Arbeit.”

- „Immer wieder beschäftigten sich in den letzten Jahren Ausstellungen mit explizit politischer Kunst. Kunst, politische Kunst, künstlerischer Aktivismus und politischer Aktivismus entwickelten sich in der Warnehmung der BetrachterInnen zu einem Knoten, dessen künstlerische Wirkmacht im formalen institutionellen Rahmen auf der Strecke blieb.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

‘Where the old is challenged by the new. Where art and theatre meet everyday and political life. It is not for nothing that artists have repeatedly called for the convergence of art and life. Because where the two collide, confrontation takes place. It is not important what exactly art is and where it begins or ends. What is relevant is that breaks are created in the smooth running of a problematic system. It is about a fracture of expectation, an interruption of the familiar. This strategy of interruption is interesting for the present work.’

- ‘In recent years, exhibitions have repeatedly focussed on explicitly political art. In the perception of viewers, art, political art, artistic activism and political activism have developed into a knot whose artistic impact has fallen by the wayside within the formal institutional framework.’

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 10.07.2014

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Konstruktive Unterbrechungen Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Seraphine Meya

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2014 01

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 30.03.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Kurzbeschreibung von Who cares?

- Titel

- Kurzbeschreibung von Who cares?

- Titel (en)

- Who cares?

- Untertitel des Projekts/Werks (en)

- Digital sociality, care infrastructure and convivial technology

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Die Hackerkultur verbindet Theorie und Praxis (nach hand-on Prinzipien) und einen neuen Ansatz für Kulturmaterialien (»information wants to be free«), der nicht nur eine andere Epistemologie, sondern auch einen neuen politischen Diskurs über Digitalität, Geräte und Menschen impliziert. Das Verhältnis zwischen Technik und Politik dieser Gruppe wird im ersten Kapitel analysiert: Zuerst wird die Entstehung proprietärer Software betrachtet, dann die Unterschiede zwischen Open Source und freier Software, und wie im letzten die Privateigentum und die soziale Beziehung zwischen Programmen, Benutzern und Entwicklern radikal in Frage gestellt werden. Später wird diese Beziehung anhand von Hanna Arendts _Die conditio humana_ in Bezug auf Arbeit, Herstellen und Handlen, Notwendigkeit und Freiheit, die die Bedingungen für Politik schaffen, weiter diskutiert. Im zweiten Kapitel wird das Konzept der Konvivialität (Ivan Illich) vorgestellt und diskutiert. Diese Idee wird später in der Wartung als infrastrukturelle Vorsorge weiterentwickelt und als ein zentrales Element digitaler Technologien vorgeschlagen, das weiter diskutiert werden sollte. Diese Konstellation des Denkens und Handelns, des Spielens und Lernens, des Experimentierens und der Übernahme von Verantwortung sowie der Politik und der sozialen Beziehungen sollte in der Technologiedebatte eine wichtige Rolle spielen.

- Beschreibung (en)

- Hacker culture connects theory and praxis (following hand-on principles) and a new approach to culture materials (»information wants to be free«), that implies not only a different epistemology, but also a new political discourse on digitality, devices, and people. The relation between technic and politic of this group is analyzed in the first chapter: first focusing on the emergence of proprietary software; then considering the differences between open source and free software, the last one challenging radically the notion of private property and the social relation among programs, users, and developers. Later on, reading Hanna Arendts "The Human condition", the relation will be further discussed in terms of labor, work and action, necessity and freedom, which establish the conditions for politics. In the second chapter, the concept of conviviality (Ivan Illich) is introduced and discussed. This idea is later developed in maintenance as infrastructural care and proposed as a central element of digital technologies that should be further discussed. This constellation of thinking and acting, playing and learning, experimenting and taking responsibility, as well as politics and social relations should play a prominent role in the debate about technology.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 30.09.2023

- Sprache

- Titel

- Kurzbeschreibung von Who cares?

- Titel (en)

- Project descritption of Who Cares?

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Víctor Fancelli Capdevila

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- Zusammenfassung des Projekts Who cares?

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 02.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Mythos Großstadt

- Titel

- Mythos Großstadt

- Untertitel

- Untersuchungen zur Stadtwahrnehmung in der Fotografie am Beispiel von Eugène Atget, Berenice Abbott und Andreas Feininger

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Paris – New York, zwei Städte, deren Namen eine Flut von Begriffen, Bildern und Assoziationen in unserem Inneren auslösen. Zwei Weltstädte, die unterschiedlicher kaum sein können. Die eine, die verträumte Stadt an der Seine, gilt als das Mekka der Liebenden, ist der Inbegriff für Kunst und Kultur, war Sitz von Königen und Kaisern wir Ludwig XIV. oder Napoleon und blutiger Schauplatz zahlreicher Revolutionen. Sie ist geprägt von einer mehr als zweitausendjährigen Geschichte und verkörpert schlichtweg das, was man heute mit französischer Lebensart verbindet. Die andere, 'die wunderbare Katastrophe', wie Le Corbusier sie nennt, besticht durch ihre schier unerschöpfliche Energie und Wandlungsfähigkeit, ihre spektakuläre Hochhausarchitektur und ihre multikulturelle Gesellschaft. Ihr Name steht für Freiheit und Selbstverwirklichung. Sie ist die Hauptstadt des Kapitalismus, aber auch ein Ort extremer sozialer Gegensätze und krimineller Energien.

Das Großstadtleben beider ist legendär und es verwundert daher nicht, dass sowohl Paris als auch New York schon früh im Brennpunkt künstlerischen bzw. fotografischen Interesses standen.”

- „Paris – New York, zwei Städte, deren Namen eine Flut von Begriffen, Bildern und Assoziationen in unserem Inneren auslösen. Zwei Weltstädte, die unterschiedlicher kaum sein können. Die eine, die verträumte Stadt an der Seine, gilt als das Mekka der Liebenden, ist der Inbegriff für Kunst und Kultur, war Sitz von Königen und Kaisern wir Ludwig XIV. oder Napoleon und blutiger Schauplatz zahlreicher Revolutionen. Sie ist geprägt von einer mehr als zweitausendjährigen Geschichte und verkörpert schlichtweg das, was man heute mit französischer Lebensart verbindet. Die andere, 'die wunderbare Katastrophe', wie Le Corbusier sie nennt, besticht durch ihre schier unerschöpfliche Energie und Wandlungsfähigkeit, ihre spektakuläre Hochhausarchitektur und ihre multikulturelle Gesellschaft. Ihr Name steht für Freiheit und Selbstverwirklichung. Sie ist die Hauptstadt des Kapitalismus, aber auch ein Ort extremer sozialer Gegensätze und krimineller Energien.

- Beschreibung (en)

- "Paris - New York, two cities whose names trigger a flood of concepts, images and associations within us. Two cosmopolitan cities that could hardly be more different. One, the dreamy city on the Seine, is considered the Mecca of lovers, is the epitome of art and culture, was the seat of kings and emperors such as Louis XIV and Napoleon and the bloody scene of numerous revolutions. It is characterized by more than two thousand years of history and simply embodies what is associated with the French way of life today. The other, 'the marvelous catastrophe', as Le Corbusier called it, captivates with its sheer inexhaustible energy and adaptability, its spectacular high-rise architecture and its multicultural society. Its name stands for freedom and self-realization. It is the capital of capitalism, but also a place of extreme social contrasts and criminal energy.

The big city life of both is legendary and it is therefore not surprising that both Paris and New York were the focus of artistic and photographic interest early on."

- "Paris - New York, two cities whose names trigger a flood of concepts, images and associations within us. Two cosmopolitan cities that could hardly be more different. One, the dreamy city on the Seine, is considered the Mecca of lovers, is the epitome of art and culture, was the seat of kings and emperors such as Louis XIV and Napoleon and the bloody scene of numerous revolutions. It is characterized by more than two thousand years of history and simply embodies what is associated with the French way of life today. The other, 'the marvelous catastrophe', as Le Corbusier called it, captivates with its sheer inexhaustible energy and adaptability, its spectacular high-rise architecture and its multicultural society. Its name stands for freedom and self-realization. It is the capital of capitalism, but also a place of extreme social contrasts and criminal energy.

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 2003

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Stadt

- Titel

- Mythos Großstadt

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Daphne Noee

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2003 02

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 16.06.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Onkel Rudi als... (Abstract)

- Titel

- Onkel Rudi als... (Abstract)

- Untertitel

- zur Werk- und Wirkungsgeschichte eines Gemäldes von Gerhard Richter im Spiegel seiner Selbstäußerungen

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Das Jahr 2012 stand ganz im Zeichen Gerhard Richters. So konnte man ihm im Kino bei der Arbeit bei der Arbeit über die Schulter schauen – so der bereits erstmals im September 2011 präsentierte Kinofilm Painting von Corinna Belz .., was einherging mit dem beachtlichen Erfolg auf dem secondary market, dem Auktionsmarkt, wo seine vornehmlich abstrakten Gemälde dank Höchstpreisen zu Kunstmarktlieblingen avancierten.”

„Gerade ein Gemälde scheint anders als viele andere in den letzten Jahren immer mehr mit symbolischer Bedeutung aufgeladen worden zu sein: Onkel Rudi (Abb.1), entstanden 1965. Die fotografische Vorlage entnahm Richter dem eigenen Familienalbum. Als ‚Privates öffentlich’ machen, wurde diese Vorgehensweise in der Motivauswahl der so genannten Foto-Bilder vielfach begründet. Dies zeigt sich nicht zuletzt in den Fotografien, die Richter auf Einladung der Tageszeitung „Die Welt” für eine Sonderausgabe ausdrucken ließ – und damit ist “der große Zweifler der Gegenwartskunst” erst der dritte Künstler, nach Georg Baselitz und Ellsworth Kelly, die die „Welt-Herrschaft” für einen Tag übernommen hat.”

- „Das Jahr 2012 stand ganz im Zeichen Gerhard Richters. So konnte man ihm im Kino bei der Arbeit bei der Arbeit über die Schulter schauen – so der bereits erstmals im September 2011 präsentierte Kinofilm Painting von Corinna Belz .., was einherging mit dem beachtlichen Erfolg auf dem secondary market, dem Auktionsmarkt, wo seine vornehmlich abstrakten Gemälde dank Höchstpreisen zu Kunstmarktlieblingen avancierten.”

- Beschreibung (en)

- "The year 2012 was all about Gerhard Richter. It was possible to watch him at work in the cinema - for example, the cinema film Painting by Corinna Belz, first presented in September 2011 ... which was accompanied by considerable success on the secondary market, the auction market, where his predominantly abstract paintings became art market favourites thanks to top prices.‘

’One painting in particular, unlike many others, seems to have been increasingly charged with symbolic meaning in recent years: Uncle Rudi (fig. 1), created in 1965. Richter took the photographic model from his own family album. This approach was often justified as “publicising the private” in the choice of motifs for the so-called photo images. This can be seen not least in the photographs that Richter had printed for a special edition at the invitation of the daily newspaper ‘Die Welt’ - making ‘the great doubter of contemporary art’ only the third artist, after Georg Baselitz and Ellsworth Kelly, to take over ‘Welt/world domination’ for a day."

- "The year 2012 was all about Gerhard Richter. It was possible to watch him at work in the cinema - for example, the cinema film Painting by Corinna Belz, first presented in September 2011 ... which was accompanied by considerable success on the secondary market, the auction market, where his predominantly abstract paintings became art market favourites thanks to top prices.‘

- Kategorie

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 15.01.2013

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Onkel Rudi als... (Abstract)

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Hendrik Bündge

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- Kurzbescheibung / Abstract

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2013 01

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 24.02.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1