Matthias Bruhn

| Name | Matthias Bruhn |

| Verzeichnis(se) |

|

77 Inhalte

- Seite 1 von 7

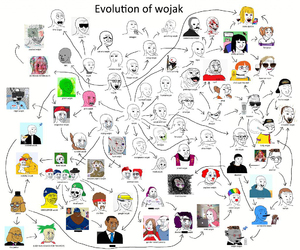

In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Titel

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Datierung

- 05.02.2025

- Titel

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Titel (en)

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts", users track the transformations of the meme.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- „Evolution of wojak”, hochgeladen auf iFunny am 24.05.2020. https://ifunny.co/picture/evolution-of-wojak-K6D6O….

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Medien-Beschreibung (en)

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts", users track the transformations of the meme.

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 08.07.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

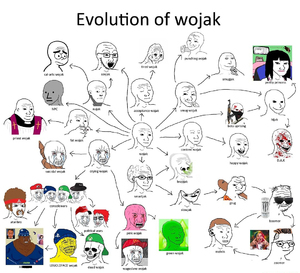

In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Titel

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Datierung

- 05.02.2025

- Titel

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Titel (en)

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts", users track the transformations of the meme.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- „Evolution of Wojak (Final)”, hochgeladen auf Know Your Meme am 04.10.2019. https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1594317-wojak.

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts" verfolgen Nutzer:innen die Entwicklung des Memes nach.

- Medien-Beschreibung (en)

- In "Wojak Evolution Charts", users track the transformations of the meme.

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 08.07.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

By Users for Users. Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Titel

- By Users for Users. Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Datierung

- 05.02.2025

- Titel

- By Users for Users. Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Titel (en)

- By Users for Users. Table of Contents

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Moritz Konrad

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 08.07.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

By Users for Users. Abstract

- Titel

- By Users for Users. Abstract

- Datierung

- 05.02.2025

- Titel

- By Users for Users. Abstract

- Titel (en)

- By Users for Users. Abstract

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Moritz Konrad

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 08.07.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Abstract

- Titel

- Abstract

- Autor/in

- Titel

- Abstract

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Josefine Scheu

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 30.06.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

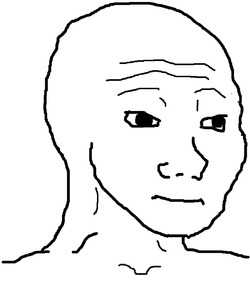

Das "Wojak"-Meme, zentrales Fallbeispiel der Magisterarbeit.

- Titel

- Das "Wojak"-Meme, zentrales Fallbeispiel der Magisterarbeit.

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 05.02.2025

- Titel

- Das "Wojak"-Meme, zentrales Fallbeispiel der Magisterarbeit.

- Titel (en)

- The "Wojak"-Meme, the central case study of the thesis.

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Unbekannt

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- Die frühste Variante des "Wojak"-Memes, auch bekannt als "Feels Guy", uploaded by an anonymous user to the Imageboard Vichan.

- Medien-Beschreibung (en)

- The earliest known variant of the "Wojak"-Meme, also known as "Feels Guy", uploaded by an anonymous user to the imageboard Vichan.

- Alternativ-Text (de)

- Eine dilettantisch erstellte digitale Zeichnung eines menschlichen Gesichts mit faltiger Stirn und einem melancholischen Gesichtsausdruck.

- Alternativ-Text (en)

- An amateurish digital drawing of a human face with a frown and a melancholy facial expression

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 25.06.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Titelblatt

- Titel

- Titelblatt

- Autor/in

- Titel

- Titelblatt

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Josefine Scheu

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 21.06.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Titel

- Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Autor/in

- Titel

- Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Josefine Scheu

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 21.06.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Abstract (updated)

- Titel

- Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Abstract (updated)

- Untertitel

- Eine Untersuchung der Beteiligung der deutschen Bundesregierung an dem NATO-Manöver Fallex 66 (1966) hinsichtlich ihrer Modalität, Fiktionalität und Immersivität.

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Fallex 66 war die dritte von zwölf biennalen Stabsrahmenübungen, die zwischen 1962 und 1982 durch die NATO organisiert wurden. Während des Kalten Krieges fanden Übungsmanöver regelmäßig statt, um mit bedingter Truppenbewegung Prozesse der Mobilisierung zu simulieren, Alarm- und Evakuierungspläne zu testen, aber auch um

Souveränität zu demonstrieren. Als solche waren sie wichtiger Teil der damaligen Abschreckungsstrategie. Die deutsche Bundesregierung beteiligte sich an diesen durch

Zivilverteidigungsübungen, um Möglichkeiten der „politischen Mitwirkung an Konsultationen und Entscheidungsfindungen der NATO auszuloten und Erfahrungen im Bereich Krisenmanagement und -kommunikation zu sammeln. Im Jahre 1966 fand diese Übung erstmals im jüngst fertiggestellten offiziellen Ausweichsitz der Bundesregierung etwa 30 Kilometer südlich von Bonn, dem Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler, statt.Neu an dieser Übung war jedoch nicht nur die Verlegung in den Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler, sondern auch der Wunsch, im Rahmen der nationalen Übung den jüngsten Entwurf für die Notstandsgesetze zu testen [...] Um den Einsatz der Notstandsgesetze im Kriegsfalle zu erproben, schritt man zu einer ungewöhnlichen Methode: 33 Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestags und des Deutschen Bundesrates simulierten als Gemeinsamer Ausschuss – das in jenem Gesetz vorgesehene legislative Gremium – für vier Tage im Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler den „gedachten Verlauf“ eines dritten Weltkrieges.”

„Die Sorge, dass durch die Implementierung der Notstandsgesetze ein Hebel zur Totalisierung des Staates juristischen Niederschlag im Grundgesetz finden könnte, wurde dabei durch das ungewöhnliche Verfahren der Übung in dem sich durch Abschottung auszeichnenden Bunker noch verstärkt. Der Aufenthalt der PolitikerInnen wurde so nicht nur Übung der Notstandsgesetze, sondern auch Symbol einer intransparent agierenden Politik. [...] Wie ich zeigen werde, werden auch der Raum der Übung und die TeilnehmerInnen selbst zu einem fiktionstragenden Medium. Deswegen stellt die Übung eine nicht-rationale, sondern affektiv und ästhetisch wirkende Form der Wissensvermittlung dar.”

- „Fallex 66 war die dritte von zwölf biennalen Stabsrahmenübungen, die zwischen 1962 und 1982 durch die NATO organisiert wurden. Während des Kalten Krieges fanden Übungsmanöver regelmäßig statt, um mit bedingter Truppenbewegung Prozesse der Mobilisierung zu simulieren, Alarm- und Evakuierungspläne zu testen, aber auch um

- Beschreibung (en)

- „How do imaginaries claim normativity? A society can only function if enough people envision the same imaginary, says Castoriadis. I claim, that new imaginaries need to be exercised, if they are to claim normative power. This paper investigates a homogenization process of a social imaginary: In the 1966 German civil defense exercise Fallex 66, 33 members of the West German parliament simulated the at this point intensely disputed Emergency Laws. This paper argues that the fusion of fictional and real elements in the exercised scenario, combined with a bodily and affective immersion in a bunker setting had the power to shift a social imaginary. By presenting the Emergency Laws in a conservative patriarchal imaginary landscape, the exercise induces a normative shift in the social perception of the Laws. This paper sheds a leftist light on the struggle, highlighting the political bias of the exercise, as well as giving a new vocabulary to the left critique of that time. With a unique conceptual set-up, this paper investigates the imaginaries transported by and the means of their production in the civil defense exercise. Hereby, I suggest a methodical set for the analysis of social imaginaries at the cutting surface of aesthetics, affect theory, contemporary history, and social philosophy.”

- Kategorie

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 03.06.2020

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Abstract (updated)

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jandra Böttger

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2020 03

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 31.03.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Einleitung

- Titel

- Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Einleitung

- Untertitel

- Eine Untersuchung der Beteiligung der deutschen Bundesregierung an dem NATO-Manöver Fallex 66 (1966) hinsichtlich ihrer Modalität, Fiktionalität und Immersivität.

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Fallex 66 war die dritte von zwölf biennalen Stabsrahmenübungen, die zwischen 1962 und 1982 durch die NATO organisiert wurden. Während des Kalten Krieges fanden Übungsmanöver regelmäßig statt, um mit bedingter Truppenbewegung Prozesse der Mobilisierung zu simulieren, Alarm- und Evakuierungspläne zu testen, aber auch um

Souveränität zu demonstrieren. Als solche waren sie wichtiger Teil der damaligen Abschreckungsstrategie. Die deutsche Bundesregierung beteiligte sich an diesen durch

Zivilverteidigungsübungen, um Möglichkeiten der „politischen Mitwirkung an Konsultationen und Entscheidungsfindungen der NATO auszuloten und Erfahrungen im Bereich Krisenmanagement und -kommunikation zu sammeln. Im Jahre 1966 fand diese Übung erstmals im jüngst fertiggestellten offiziellen Ausweichsitz der Bundesregierung etwa 30 Kilometer südlich von Bonn, dem Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler, statt.Neu an dieser Übung war jedoch nicht nur die Verlegung in den Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler, sondern auch der Wunsch, im Rahmen der nationalen Übung den jüngsten Entwurf für die Notstandsgesetze zu testen [...] Um den Einsatz der Notstandsgesetze im Kriegsfalle zu erproben, schritt man zu einer ungewöhnlichen Methode: 33 Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestags und des Deutschen Bundesrates simulierten als Gemeinsamer Ausschuss – das in jenem Gesetz vorgesehene legislative Gremium – für vier Tage im Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler den „gedachten Verlauf“ eines dritten Weltkrieges.”

„Die Sorge, dass durch die Implementierung der Notstandsgesetze ein Hebel zur Totalisierung des Staates juristischen Niederschlag im Grundgesetz finden könnte, wurde dabei durch das ungewöhnliche Verfahren der Übung in dem sich durch Abschottung auszeichnenden Bunker noch verstärkt. Der Aufenthalt der PolitikerInnen wurde so nicht nur Übung der Notstandsgesetze, sondern auch Symbol einer intransparent agierenden Politik. [...] Wie ich zeigen werde, werden auch der Raum der Übung und die TeilnehmerInnen selbst zu einem fiktionstragenden Medium. Deswegen stellt die Übung eine nicht-rationale, sondern affektiv und ästhetisch wirkende Form der Wissensvermittlung dar.”

- „Fallex 66 war die dritte von zwölf biennalen Stabsrahmenübungen, die zwischen 1962 und 1982 durch die NATO organisiert wurden. Während des Kalten Krieges fanden Übungsmanöver regelmäßig statt, um mit bedingter Truppenbewegung Prozesse der Mobilisierung zu simulieren, Alarm- und Evakuierungspläne zu testen, aber auch um

- Beschreibung (en)

- „How do imaginaries claim normativity? A society can only function if enough people envision the same imaginary, says Castoriadis. I claim, that new imaginaries need to be exercised, if they are to claim normative power. This paper investigates a homogenization process of a social imaginary: In the 1966 German civil defense exercise Fallex 66, 33 members of the West German parliament simulated the at this point intensely disputed Emergency Laws. This paper argues that the fusion of fictional and real elements in the exercised scenario, combined with a bodily and affective immersion in a bunker setting had the power to shift a social imaginary. By presenting the Emergency Laws in a conservative patriarchal imaginary landscape, the exercise induces a normative shift in the social perception of the Laws. This paper sheds a leftist light on the struggle, highlighting the political bias of the exercise, as well as giving a new vocabulary to the left critique of that time. With a unique conceptual set-up, this paper investigates the imaginaries transported by and the means of their production in the civil defense exercise. Hereby, I suggest a methodical set for the analysis of social imaginaries at the cutting surface of aesthetics, affect theory, contemporary history, and social philosophy.”

- Kategorie

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 03.06.2020

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Einleitung

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jandra Böttger

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2020 03

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 30.03.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Titel

- Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Untertitel

- Eine Untersuchung der Beteiligung der deutschen Bundesregierung an dem NATO-Manöver Fallex 66 (1966) hinsichtlich ihrer Modalität, Fiktionalität und Immersivität.

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- „Fallex 66 war die dritte von zwölf biennalen Stabsrahmenübungen, die zwischen 1962 und 1982 durch die NATO organisiert wurden. Während des Kalten Krieges fanden Übungsmanöver regelmäßig statt, um mit bedingter Truppenbewegung Prozesse der Mobilisierung zu simulieren, Alarm- und Evakuierungspläne zu testen, aber auch um

Souveränität zu demonstrieren. Als solche waren sie wichtiger Teil der damaligen Abschreckungsstrategie. Die deutsche Bundesregierung beteiligte sich an diesen durch

Zivilverteidigungsübungen, um Möglichkeiten der „politischen Mitwirkung an Konsultationen und Entscheidungsfindungen der NATO auszuloten und Erfahrungen im Bereich Krisenmanagement und -kommunikation zu sammeln. Im Jahre 1966 fand diese Übung erstmals im jüngst fertiggestellten offiziellen Ausweichsitz der Bundesregierung etwa 30 Kilometer südlich von Bonn, dem Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler, statt.Neu an dieser Übung war jedoch nicht nur die Verlegung in den Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler, sondern auch der Wunsch, im Rahmen der nationalen Übung den jüngsten Entwurf für die Notstandsgesetze zu testen [...] Um den Einsatz der Notstandsgesetze im Kriegsfalle zu erproben, schritt man zu einer ungewöhnlichen Methode: 33 Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestags und des Deutschen Bundesrates simulierten als Gemeinsamer Ausschuss – das in jenem Gesetz vorgesehene legislative Gremium – für vier Tage im Regierungsbunker Ahrweiler den „gedachten Verlauf“ eines dritten Weltkrieges.”

„Die Sorge, dass durch die Implementierung der Notstandsgesetze ein Hebel zur Totalisierung des Staates juristischen Niederschlag im Grundgesetz finden könnte, wurde dabei durch das ungewöhnliche Verfahren der Übung in dem sich durch Abschottung auszeichnenden Bunker noch verstärkt. Der Aufenthalt der PolitikerInnen wurde so nicht nur Übung der Notstandsgesetze, sondern auch Symbol einer intransparent agierenden Politik. [...] Wie ich zeigen werde, werden auch der Raum der Übung und die TeilnehmerInnen selbst zu einem fiktionstragenden Medium. Deswegen stellt die Übung eine nicht-rationale, sondern affektiv und ästhetisch wirkende Form der Wissensvermittlung dar.”

- „Fallex 66 war die dritte von zwölf biennalen Stabsrahmenübungen, die zwischen 1962 und 1982 durch die NATO organisiert wurden. Während des Kalten Krieges fanden Übungsmanöver regelmäßig statt, um mit bedingter Truppenbewegung Prozesse der Mobilisierung zu simulieren, Alarm- und Evakuierungspläne zu testen, aber auch um

- Beschreibung (en)

- „How do imaginaries claim normativity? A society can only function if enough people envision the same imaginary, says Castoriadis. I claim, that new imaginaries need to be exercised, if they are to claim normative power. This paper investigates a homogenization process of a social imaginary: In the 1966 German civil defense exercise Fallex 66, 33 members of the West German parliament simulated the at this point intensely disputed Emergency Laws. This paper argues that the fusion of fictional and real elements in the exercised scenario, combined with a bodily and affective immersion in a bunker setting had the power to shift a social imaginary. By presenting the Emergency Laws in a conservative patriarchal imaginary landscape, the exercise induces a normative shift in the social perception of the Laws. This paper sheds a leftist light on the struggle, highlighting the political bias of the exercise, as well as giving a new vocabulary to the left critique of that time. With a unique conceptual set-up, this paper investigates the imaginaries transported by and the means of their production in the civil defense exercise. Hereby, I suggest a methodical set for the analysis of social imaginaries at the cutting surface of aesthetics, affect theory, contemporary history, and social philosophy.”

- Kategorie

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 03.06.2020

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Titel

- Die Übung eines gesellschaftlichen Imaginären Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Jandra Böttger

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Archiv-Signatur

- HfG HS 2020 03

- Externes Archiv

- Importiert am

- 30.03.2025

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

Arbeitstisch - Zettelkasten

- Titel

- Arbeitstisch - Zettelkasten

- Autor/in

- Titel

- Arbeitstisch - Zettelkasten

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- © Kristina Moser

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Freigabe Nutzung HfG

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Medien-Beschreibung

- Der Zettelkasten ist das Herzstück der Sammlung und befindet sich auf einem Tisch, wo er durchblättert und erforscht werden kann. Der Inhalt des Zettelkastens steht in Zusammenhang mit den Bildern der Memowand und ist deswegen so positioniert, dass Blickkontakt zwischen dem Zettelkasten und den Bildern aufgenommen werden kann.

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Typ der Abschlussarbeit

- Importiert am

- 07.08.2024

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1