"Bühnenbild"

| Begriff | Bühnenbild |

| Metakey | Schlagworte (madek_core:keywords) |

| Typ | Keyword |

| Vokabular | Madek Core |

51 Inhalte

- Seite 1 von 5

MAS 003

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Untertitel

- László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

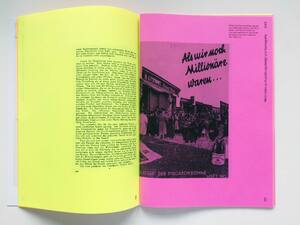

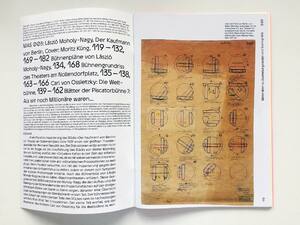

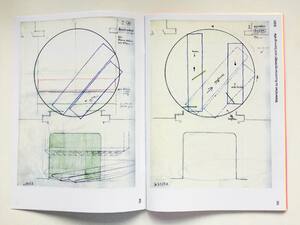

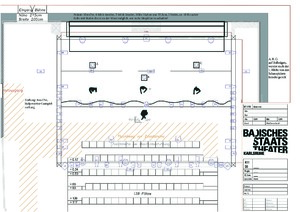

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

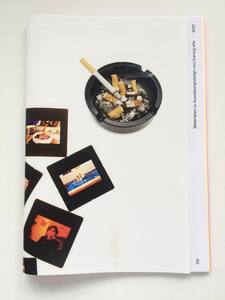

Der Umschlag des 3. MAS Heftes wurde von dem Kurator Moritz Küng gestaltet. Eingeladen auf dem Cover zum Begriff „Darstellungspolitik“ Stellung zu nehmen und inspiriert vom Titel des Magazins, musste Küng daran denken, wie sich vor rund 25 Jahren ein guter Freund – ein Anwalt für Mietrecht – bei ihm beklagte, dass er als leidenschaftlicher Fotograf eigentlich lieber Künstler geworden wäre. In einer Mischung aus Wehmut und Frustration kommentierte er im Schweizer Dialekt den Beruf des Kuratoren wie folgt: “Aber was machsch du eigentlech: Käffeli trinke, Zigarettli rauche ond Föteli luege”. Dementsprechend illustrierte Küng den Beruf des Kurators mit im Internet gefundenen Stock-Fotos (Kaffeetasse, Aschenbecher, Dias).

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

- Beschreibung (en)

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

The cover of the 3rd issue of MAS was designed by curator Moritz Küng. Invited to comment on the term "politics of representation" on the cover and inspired by the title of the magazine, Küng was reminded of how, around 25 years ago, a good friend - a lawyer specializing in tenancy law - complained to him that, as a passionate photographer, he would actually have preferred to become an artist. In a mixture of melancholy and frustration, he commented on the profession of curator in Swiss dialect as follows: "But what do you actually do: drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and listen to fiddles". Accordingly, Küng illustrated the curator's profession with stock photos found on the Internet (coffee cup, ashtray, slides).

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Abmessungen

- DIN A4

- Ort: Institution

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

68 Seiten

28 Abb., farbig

Cover: Moritz Küng

Abbildungen: Bühnenentwürfe von L. Moholy-Nagy, Programmheft der Piscator Bühne, Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung der Universität Köln

Grafik Credits: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Fachbereich Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie, HfG Karlsruhe; Cover: Moritz Küng; Grafik: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 24.05.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

MAS 003

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Untertitel

- László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

Der Umschlag des 3. MAS Heftes wurde von dem Kurator Moritz Küng gestaltet. Eingeladen auf dem Cover zum Begriff „Darstellungspolitik“ Stellung zu nehmen und inspiriert vom Titel des Magazins, musste Küng daran denken, wie sich vor rund 25 Jahren ein guter Freund – ein Anwalt für Mietrecht – bei ihm beklagte, dass er als leidenschaftlicher Fotograf eigentlich lieber Künstler geworden wäre. In einer Mischung aus Wehmut und Frustration kommentierte er im Schweizer Dialekt den Beruf des Kuratoren wie folgt: “Aber was machsch du eigentlech: Käffeli trinke, Zigarettli rauche ond Föteli luege”. Dementsprechend illustrierte Küng den Beruf des Kurators mit im Internet gefundenen Stock-Fotos (Kaffeetasse, Aschenbecher, Dias).

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

- Beschreibung (en)

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

The cover of the 3rd issue of MAS was designed by curator Moritz Küng. Invited to comment on the term "politics of representation" on the cover and inspired by the title of the magazine, Küng was reminded of how, around 25 years ago, a good friend - a lawyer specializing in tenancy law - complained to him that, as a passionate photographer, he would actually have preferred to become an artist. In a mixture of melancholy and frustration, he commented on the profession of curator in Swiss dialect as follows: "But what do you actually do: drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and listen to fiddles". Accordingly, Küng illustrated the curator's profession with stock photos found on the Internet (coffee cup, ashtray, slides).

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Abmessungen

- DIN A4

- Ort: Institution

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

68 Seiten

28 Abb., farbig

Cover: Moritz Küng

Abbildungen: Bühnenentwürfe von L. Moholy-Nagy, Programmheft der Piscator Bühne, Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung der Universität Köln

Grafik Credits: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Fachbereich Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie, HfG Karlsruhe; Cover: Moritz Küng; Grafik: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 24.05.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

MAS 003

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Untertitel

- László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

Der Umschlag des 3. MAS Heftes wurde von dem Kurator Moritz Küng gestaltet. Eingeladen auf dem Cover zum Begriff „Darstellungspolitik“ Stellung zu nehmen und inspiriert vom Titel des Magazins, musste Küng daran denken, wie sich vor rund 25 Jahren ein guter Freund – ein Anwalt für Mietrecht – bei ihm beklagte, dass er als leidenschaftlicher Fotograf eigentlich lieber Künstler geworden wäre. In einer Mischung aus Wehmut und Frustration kommentierte er im Schweizer Dialekt den Beruf des Kuratoren wie folgt: “Aber was machsch du eigentlech: Käffeli trinke, Zigarettli rauche ond Föteli luege”. Dementsprechend illustrierte Küng den Beruf des Kurators mit im Internet gefundenen Stock-Fotos (Kaffeetasse, Aschenbecher, Dias).

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

- Beschreibung (en)

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

The cover of the 3rd issue of MAS was designed by curator Moritz Küng. Invited to comment on the term "politics of representation" on the cover and inspired by the title of the magazine, Küng was reminded of how, around 25 years ago, a good friend - a lawyer specializing in tenancy law - complained to him that, as a passionate photographer, he would actually have preferred to become an artist. In a mixture of melancholy and frustration, he commented on the profession of curator in Swiss dialect as follows: "But what do you actually do: drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and listen to fiddles". Accordingly, Küng illustrated the curator's profession with stock photos found on the Internet (coffee cup, ashtray, slides).

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Abmessungen

- DIN A4

- Ort: Institution

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

68 Seiten

28 Abb., farbig

Cover: Moritz Küng

Abbildungen: Bühnenentwürfe von L. Moholy-Nagy, Programmheft der Piscator Bühne, Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung der Universität Köln

Grafik Credits: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Fachbereich Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie, HfG Karlsruhe; Cover: Moritz Küng; Grafik: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 24.05.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

MAS 003

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Untertitel

- László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

Der Umschlag des 3. MAS Heftes wurde von dem Kurator Moritz Küng gestaltet. Eingeladen auf dem Cover zum Begriff „Darstellungspolitik“ Stellung zu nehmen und inspiriert vom Titel des Magazins, musste Küng daran denken, wie sich vor rund 25 Jahren ein guter Freund – ein Anwalt für Mietrecht – bei ihm beklagte, dass er als leidenschaftlicher Fotograf eigentlich lieber Künstler geworden wäre. In einer Mischung aus Wehmut und Frustration kommentierte er im Schweizer Dialekt den Beruf des Kuratoren wie folgt: “Aber was machsch du eigentlech: Käffeli trinke, Zigarettli rauche ond Föteli luege”. Dementsprechend illustrierte Küng den Beruf des Kurators mit im Internet gefundenen Stock-Fotos (Kaffeetasse, Aschenbecher, Dias).

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

- Beschreibung (en)

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

The cover of the 3rd issue of MAS was designed by curator Moritz Küng. Invited to comment on the term "politics of representation" on the cover and inspired by the title of the magazine, Küng was reminded of how, around 25 years ago, a good friend - a lawyer specializing in tenancy law - complained to him that, as a passionate photographer, he would actually have preferred to become an artist. In a mixture of melancholy and frustration, he commented on the profession of curator in Swiss dialect as follows: "But what do you actually do: drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and listen to fiddles". Accordingly, Küng illustrated the curator's profession with stock photos found on the Internet (coffee cup, ashtray, slides).

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Abmessungen

- DIN A4

- Ort: Institution

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

68 Seiten

28 Abb., farbig

Cover: Moritz Küng

Abbildungen: Bühnenentwürfe von L. Moholy-Nagy, Programmheft der Piscator Bühne, Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung der Universität Köln

Grafik Credits: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Fachbereich Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie, HfG Karlsruhe; Cover: Moritz Küng; Grafik: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 24.05.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

MAS 003

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Untertitel

- László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

Der Umschlag des 3. MAS Heftes wurde von dem Kurator Moritz Küng gestaltet. Eingeladen auf dem Cover zum Begriff „Darstellungspolitik“ Stellung zu nehmen und inspiriert vom Titel des Magazins, musste Küng daran denken, wie sich vor rund 25 Jahren ein guter Freund – ein Anwalt für Mietrecht – bei ihm beklagte, dass er als leidenschaftlicher Fotograf eigentlich lieber Künstler geworden wäre. In einer Mischung aus Wehmut und Frustration kommentierte er im Schweizer Dialekt den Beruf des Kuratoren wie folgt: “Aber was machsch du eigentlech: Käffeli trinke, Zigarettli rauche ond Föteli luege”. Dementsprechend illustrierte Küng den Beruf des Kurators mit im Internet gefundenen Stock-Fotos (Kaffeetasse, Aschenbecher, Dias).

- Die dritte Ausgabe von ‚Materialien zu Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie‘ ist der Bühnengestaltung von László Moholy-Nagy für Erwin Piscators Inszenierung des Stückes “Der Kaufmann von Berlin” von 1929 gewidmet. Die Inszenierung wurde nicht nur aufgrund der politischen Inhalte zum Skandal, auch die von der Presse als „Maschinentheater“ bezeichnete Szenografie erregte Aufsehen. Die formalen Mittel, die Moholy-Nagy in seinen Bühnenbildern für Piscator einsetzte – wie Laufbänder, mobile Stahlgestänge, Licht- und Schattenspiele, Film- und Diaprojektionen – übertrug er 1930 in seine „Ausstellungsszenografien“ für den Theaterbereich der Werkbundausstellung beim Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris sowie in seinen Entwurf des „Raums der Gegenwart“ für das Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. Die Radikalität von Moholy-Nagys Bühnenentwürfen geht aus den bekannten Szenenfotos von Lotte Jacobi kaum hervor. Daher umfasst das vorliegende Heft 28 von Moholy-Nagy gezeichnete Bühnenpläne, welche den bühnentechnischen Ablauf des Stückes nachvollziehbar machen, das Programmheft mit Umschlaggestaltung und Fotografien des Bühnenmodells ebenfalls von Moholy-Nagy, sowie eine ausführliche Rezension von Carl von Ossietzky, erschienen 1929 in der Weltbühne.

- Beschreibung (en)

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

The cover of the 3rd issue of MAS was designed by curator Moritz Küng. Invited to comment on the term "politics of representation" on the cover and inspired by the title of the magazine, Küng was reminded of how, around 25 years ago, a good friend - a lawyer specializing in tenancy law - complained to him that, as a passionate photographer, he would actually have preferred to become an artist. In a mixture of melancholy and frustration, he commented on the profession of curator in Swiss dialect as follows: "But what do you actually do: drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and listen to fiddles". Accordingly, Küng illustrated the curator's profession with stock photos found on the Internet (coffee cup, ashtray, slides).

- The third edition of 'Materials on Exhibition Design and Scenography' is dedicated to László Moholy-Nagy's stage design for Erwin Piscator's 1929 production of the play "The Merchant of Berlin". The production became a scandal not only because of its political content, but also because the scenography, which the press described as "machine theater", caused a sensation. The formal means that Moholy-Nagy used in his stage designs for Piscator - such as treadmills, mobile steel rods, plays of light and shadow, film and slide projections - were transferred to his "exhibition scenographies" for the theater section of the Werkbund exhibition at the Salon des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1930 and to his design of the "Raum der Gegenwart" for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. The radical nature of Moholy-Nagy's stage designs hardly emerges from the well-known scene photos by Lotte Jacobi. This booklet therefore contains 28 stage plans drawn by Moholy-Nagy, which make the technical stage sequence of the play comprehensible, the program booklet with cover design and photographs of the stage model, also by Moholy-Nagy, as well as a detailed review by Carl von Ossietzky, published in the Weltbühne in 1929.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Abmessungen

- DIN A4

- Ort: Institution

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

68 Seiten

28 Abb., farbig

Cover: Moritz Küng

Abbildungen: Bühnenentwürfe von L. Moholy-Nagy, Programmheft der Piscator Bühne, Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung der Universität Köln

Grafik Credits: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Heft 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Der Kaufmann von Berlin

- Titel

- MAS 003

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Fachbereich Ausstellungsdesign und Szenografie, HfG Karlsruhe; Cover: Moritz Küng; Grafik: Johannes Hucht, Yannick Nuss

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 24.05.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Paula Klotzki und Cara Kollmann

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Paula Klotzki und Cara Kollmann

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Paula Klotzki und Cara Kollmann

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Paula Klotzki und Cara Kollmann

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Paula Klotzki und Cara Kollmann

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Paula Klotzki und Cara Kollmann

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung