"Plakat zur Aufführung"

| Begriff | Plakat zur Aufführung |

| Metakey | Beziehung/Funktion (media_object:relationship) |

| Typ | Keyword |

| Vokabular | Medienobjekt |

4 Inhalte

- Seite 1 von 1

DNS #69

- Titel

- DNS #69

- Untertitel

- Fischer Fritz

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Frische Fische kann Fischer Fritz nicht mehr fischen. Nicht erst seit seinem Schlaganfall. Sein Sohn Franz ist kein Fischer geworden, sondern Frisör in der Großstadt. Um den Vater zu versorgen hat er eine ausländische Pflegekraft engagiert. Ein Sprechtheater nennt die Autorin Raphaela Bardutzky ihr Stück, das bei den Autor*innentheatertage 2022 am Deutschen Theater in Berlin ausgezeichnet wurde. Sprachlich virtuos, tragisch-komisch und spielerisch leicht erzählt sie von Heimat und Fremde, Sehnsucht und Einsamkeit, Stadt und Land, Alter und Jugend. Im Anschluss findet ein Gespräch mit der Autorin Raphaela Bardutzky statt.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

Fisherman Fritz can no longer catch fresh fish. Not just since his stroke. His son Franz has not become a fisherman, but a hairdresser in the big city. He has hired a foreign carer to look after his father. Author Raphaela Bardutzky calls her play, which won an award at the Autor*innentheatertage 2022 at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin, spoken theater. With virtuoso language, tragic-comic and playful lightness, it tells of home and foreignness, longing and loneliness, city and country, age and youth. This will be followed by a discussion with the author Raphaela Bardutzky.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 04.02.2023

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Großes Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Beteiligte Institution(en)

- Titel

- DNS #69

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Ines Bohnert

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 20.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

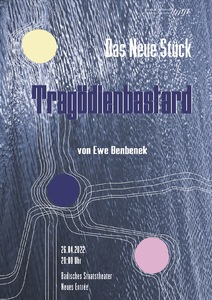

DNS #68

- Titel

- DNS #68

- Untertitel

- Tragödienbastard

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

- Es ist ein Akt der Emanzipation. Das mit dem Mühlheimer Dramatikerpreis gekrönte Stück erzählt in einem rhythmisch tobenden Redestrom davon, wie sich die Tochter polnischer Einwanderer und ihre „chosen sisters“ von der Last des Migrationsnarrativs befreien und zu dem werden, was sie eigentlich immer waren: Göttinnen.

Das Stück “Tragödienbastard” von Ewe Benbenek wurde im Wintersemester 2021/2022 im Rahmen des Seminars ‘Das neue Stück’ von Studierenden technisch und künstlerisch erarbeitet und in eine knapp zweistündige szenische Lesung umgesetzt. Das Projekt wurde von Constanze Fischbeck, Anna Haas und Eivind Haugland betreut sowie von Sandra Blatterer, welche in einem einwöchigen Lichtworkshop spannende Impulse zur Erarbeitung des Licht- und Bühnenkonzepts gab.

Im Anschluss an die szenische Lesung findet ein Nachgespräch mit der Autorin Ewe Benbenek und den Mitwirkenden statt.

- Es ist ein Akt der Emanzipation. Das mit dem Mühlheimer Dramatikerpreis gekrönte Stück erzählt in einem rhythmisch tobenden Redestrom davon, wie sich die Tochter polnischer Einwanderer und ihre „chosen sisters“ von der Last des Migrationsnarrativs befreien und zu dem werden, was sie eigentlich immer waren: Göttinnen.

- Beschreibung (en)

- It is an act of emancipation. The play, which was awarded the Mühlheim Dramatist Prize, tells the story of how the daughter of Polish immigrants and her "chosen sisters" free themselves from the burden of the migration narrative in a rhythmically raging stream of speech and become what they actually always were: Goddesses.

The play "Tragödienbastard" by Ewe Benbenek was technically and artistically developed by students in the winter semester 2021/2022 as part of the seminar 'Das neue Stück' and transformed into a staged reading lasting almost two hours. The project was supervised by Constanze Fischbeck, Anna Haas and Eivind Haugland as well as Sandra Blatterer, who gave exciting impulses for the development of the lighting and stage concept in a one-week lighting workshop.

The staged reading will be followed by a discussion with the author Ewe Benbenek and the participants.

- It is an act of emancipation. The play, which was awarded the Mühlheim Dramatist Prize, tells the story of how the daughter of Polish immigrants and her "chosen sisters" free themselves from the burden of the migration narrative in a rhythmically raging stream of speech and become what they actually always were: Goddesses.

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 26.04.2022

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Dauer

- 2 Stunden

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- neues Entrée

- Stadt

- Land

- Beteiligte Institution(en)

- Titel

- DNS #68

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Amelie Enders und Elisabeth Bayerl

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 20.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

DNS #64

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Untertitel

- Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Das neue Stück „Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes“ handelt von der ersten Programmiererin der Welt, Ada Lovelace. Es beschreibt Adas Leben in zwei Teilen: Einem biografischen aber stark verfremdeten ersten Teil, der durch seine Dialoge und Besetzung eher Traumhaft wirkt, und einem realistisch anmutenden zweiten Teil, in dem eine Zukunft erdacht wird, in der eine der Maschinen, die Ada einst erfand, die Macht über die Menschheit an sich nimmt.

Unsere Kulisse bestand aus einem leicht durchscheinenden Vorhang, der die Bühne in der Mitte teilt. Im ersten Teil des Stücks saßen die Zuschauer auf der Tribüne, für den zweiten Teil wechselten sie die Seite des Vorhangs und saßen dann auf niedrigen Podesten auf der Rückseite der Bühne.

Um die Traumhaftigkeit des ersten Teils darzustellen, zeigten wir dort nur die Schauspielerin von Ada vor dem Vorhang, die anderen drei Schauspieler, welche die Figuren der Mutter und zweier Puppen darstellten, befanden sich hinter dem Vorhang und waren nur durch Schatten auf diesem zu sehen. Das Stück lässt offen, ob Ada mit echten Personen spricht, ob die Ereignisse wirklich passiert sind, oder ob alles nur in Adas Kopf stattfindet. Dieses Verschwimmen aus Fiebertraum und Wirklichkeit wurde durch die Schatten auf dem Vorhang artikuliert. Um dem Publikum dennoch ein Gefühl für die echte Ada Lovelace zu geben, wurden immer wieder Fakten aus ihrem Leben auf den Vorhang projiziert.

Im zweiten, sehr realistisch anmutenden Teil, bei dem sich die Zuschauer auf der anderen Seite des Vorhangs befinden, stehen die drei Schauspieler nun auf der Publikumsseite des Vorhangs in den Rollen dreier Wissenschaftler. Ada, jetzt als Roboter, steht leicht beleuchtet hinter dem Vorhang und scheint wie eine Traumvorstellung trüb durch den Stoff. In dem Moment, als sie zu eigenständigem Leben erwacht, wechselt sie die Seite des Vorhangs, tritt aus dem Traum und übernimmt die Realität.

Neben dem Verschwimmen von Traum und Realität, ist das Stück ebenfalls geprägt von Machtverhältnissen: Im ersten Teil wird Ada von ihrer Mutter und ihren vielen Krankheiten dominiert und muss viel liegen. Die Schauspielerin sitzt im gesamten ersten Teil auf dem Boden. Der Schatten der Mutter hinter ihr ist groß und bedrohlich. Das Publikum sitzt in einer erhöhten Position auf der Tribüne und schaut auf Ada herab.

Im zweiten Teil übernimmt Ada in Form eines Roboters die Macht, das Publikum wird ihr untergeordnet und sitzt auf niedrigen Podesten fast auf dem Boden. Die Wissenschaftler werden von Ada überwunden und verlassen nach und nach den Lichtkegel der Bühne.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

The new play "Frau Ada denkt Unerhörtes" is about the world's first female programmer, Ada Lovelace. It describes Ada's life in two parts: A biographical but heavily distorted first part, which seems rather dreamlike due to its dialog and cast, and a realistic-seeming second part, in which a future is imagined in which one of the machines Ada once invented takes power over humanity.

Our backdrop consisted of a slightly translucent curtain that divided the stage in the middle. In the first part of the play, the audience sat on the bleachers; for the second part, they changed sides of the curtain and then sat on low platforms at the back of the stage.

In order to portray the dreamlike nature of the first part, we only showed Ada's actress in front of the curtain; the other three actors, who played the characters of the mother and two puppets, were behind the curtain and could only be seen through shadows on it. The play leaves it open as to whether Ada is talking to real people, whether the events really happened or whether everything is just taking place in Ada's head. This blurring of fever dream and reality was articulated by the shadows on the curtain. In order to give the audience a feeling for the real Ada Lovelace, facts from her life were projected onto the curtain again and again.

In the second, very realistic-looking part, in which the audience is on the other side of the curtain, the three actors now stand on the audience side of the curtain in the roles of three scientists. Ada, now as a robot, stands slightly illuminated behind the curtain and seems to be clouding through the fabric like a dream. The moment she awakens to independent life, she changes sides of the curtain, steps out of the dream and takes over reality.

In addition to the blurring of dream and reality, the play is also characterized by power relations: In the first part, Ada is dominated by her mother and her many illnesses and has to lie down a lot. The actress sits on the floor throughout the first part. The shadow of her mother behind her is large and threatening. The audience sits in an elevated position on the stand and looks down on Ada.

In the second part, Ada takes over in the form of a robot, the audience is subordinated to her and sits on low platforms almost on the floor. The scientists are overcome by Ada and gradually leave the light cone of the stage.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 16.01.2020

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studiobühne

- Stadt

- Land

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne & Kostüme: Paula Klotzki, Cara Kollmann

Regie: Liss Scholtes

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Anna Gesa-Raija Lappe, Tom Gramenz, Gunnar Schmidt

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #64

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Paula Klotzki und Cara Kollmann

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1

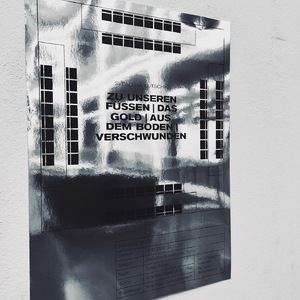

DNS #63

- Titel

- DNS #63

- Untertitel

- Zu unseren Füßen, das Gold, aus dem Boden Verschwunden

- Autor/in

- Beschreibung (de)

-

Ein Wohnhaus in Berlin: darin ein alter Trinker, ein lesbisches Paar, ein Geflüchteter, eine depressive Frau und ihr Ex-Mann. Im Stück „Zu unseren Füßen, das Gold, aus dem Boden verschwunden“ von Svealena Kutschke entspinnen sich im Alltag jener Figuren Fragen nach unserem Umgang mit dem Fremdem – sei es kultureller oder ideologischer Couleur. Die voyeuristische Situation, in welcher sich jegliche Erkenntnis nur durch die Blicke und Zuschreibungen der Nachbarn vollzieht, wurde hierfür in eine panoptische Szenografie übersetzt. Darin bewohnen die Schauspieler gemeinsam mit den Zuschauern Vorder- und Hinterhaus sowie die Seitenflügel, um so gleichsam eine diskursive wie affizierende Arena aufzuspannen. In der Mitte, ein Spiegel. Jene Leerstelle fungiert zugleich – in Form des Hinterhofs – als Austragungsort der einsamen Monologe wie auch als räumlicher Akteur für den, in der Besetzung nicht vorgesehenen, Flüchtling. Ob und wie jene Figur durch die Spiegelreflexion eine Stimme erlangt oder ob die Anwesenden in der Betrachtung lediglich auf sich selbst zurückgeworfen werden, bleibt bewusst eine offene, ungelöste Frage.

-

- Beschreibung (en)

-

An apartment building in Berlin: an old drunk, a lesbian couple, a refugee, a depressed woman and her ex-husband. In Svealena Kutschke's play "Zu unseren Füßen, das Gold, aus dem Boden verschwunden" (At our feet, the gold that has disappeared from the ground), questions about how we deal with the foreign - be it of a cultural or ideological nature - arise in the everyday lives of these characters. The voyeuristic situation, in which all knowledge is only gained through the gazes and attributions of the neighbors, was translated into a panoptic scenography. In it, the actors inhabit the front and back houses as well as the side wings together with the audience in order to create an arena that is both discursive and affirmative. In the middle, a mirror. This empty space functions simultaneously - in the form of the backyard - as a venue for the solitary monologues and as a spatial actor for the refugee, who is not included in the cast. Whether and how this figure acquires a voice through the mirror reflection or whether those present are merely thrown back on themselves in the reflection deliberately remains an open, unresolved question.

-

- Typ des Projekts/Werks

- Schlagworte

- Datierung

- 13.12.2019

- Mitwirkende

- Sprache

- Ort: Institution

- Ort

- Studio

- Stadt

- Land

- Beteiligte Institution(en)

- Bemerkungen

- Szenische Lesung

Bühne: Julia Ihls und Gloria Müller, ADSZ Hfg Karslruhe WS 2019/2020

Regie: Tobias Dömer

Dramaturgie: Nele Lindemann, Anna Haas

Mit: Ute Baggeröhr, Marie-Joelle Blazejewski, Antonia Mohr, Sven Daniel Bühler, Timo Tank

- Szenische Lesung

- Titel

- DNS #63

- Urheberrechtshinweis

- Julia Ihls

- Rechtsschutz/Lizenz

- Medienersteller/in

- Beziehung/Funktion

- Projektleiter/in

- Semester

- Studiengang

- Lehrveranstaltung

- Importiert am

- 19.12.2023

- Übergeordnete Sets

- 1